|

Evelyn Ruth Ordman had a way of

getting what she

wanted.

She talked

a famous jazz musician into donating untold hours to teach

schoolchildren about music. She arranged for a papal intervention that

resulted in a donation of land for a school playground. She even

persuaded children to pass up trick-or-treat candy to campaign for her

election as precinct chairman.

"She was like a Mother Teresa. She

wants

something

done, she doesn't yell, she just comes and talks to you and bam, it

gets done," said Keter Betts, the renown bassist, laughing at the

memory of how Ordman sweet-talked him into volunteering. "These type of

people are very, very rare. They come in and see the world and they see

where deficiencies are, and they plug the holes."

Ordman, who died Feb. 21 of

complications from

cancer

at age 90, spent most of her life convinced of the importance of the

arts. In 1937, shortly after graduating with a degree in literary

interpretation from Emerson College, she took a job as a traveling

theatrical producer and director, the dramatic equivalent of Professor

Harold Hill of "The Music Man." She was sent to Maryland's Eastern

Shore and landed in Willards, halfway between Salisbury and Ocean City.

To drum up interest in a show, she decided to stage a parade. She had

animal costumes for the children but had no clown outfits for the

adults. Her son, Edward Ordman, recounted her tale on his Web site.

"Then one of the men spoke up.

"Look, we get the

idea.

You want a big, fancy, parade, with lots of costumes, and you want

everyone in town to come watch the parade and have a good time, right?"

"Yes."

"OK, you leave it to us. We know

what to do, you

don't worry, just come tomorrow, and we'll give you a real nice parade.

"The parade the next day was, by

later reports,

the

biggest in that part of the Eastern Shore for a long time. It had all

the circus costumes except the clowns, quite a few children dressed as

midgets and animals, six fire engines constituting the entire fire

departments of four nearby towns, and, in place of the clowns, what

looked to Evelyn like 50 Ku Klux Klan members in full Klan regalia and

carrying a large cross."

The KKK joined a parade staged by a

diminutive

Northern woman, who was Jewish.

Ordman married a few years later,

and after

World War

II, she and her husband, Arnold, settled in Montgomery County. She

became involved in the Montgomery County public schools, first as a

volunteer and later developing cultural enrichment programs for

children with federal money. She noticed that African American children

rarely saw successful black professionals at their schools. So in the

early 1960s, she invited Betts, who has a home in Montgomery and had

children in several local schools, to give a performance. He tried to

say no, but she kept solving the problems he raised.

"She kept after me for about two

weeks, in that

little

Katharine Hepburn style," Betts said. When he finally appeared at

Washington Grove Elementary in Gaithersburg, the students' response

hooked him: "I went up to the school, and it was amazing. It just

floored me."

It's unclear whether Ordman knew

that she was

twisting

a world-famous arm, one that played with Dinah Washington, Ella

Fitzgerald, Woody Herman, Charlie Parker, among others. Nevertheless,

Betts did about 100 performances a year just for schoolchildren, and

with the Wolf Trap Foundation for the Performing Arts started a program

to bring preschool children in Head Start to special performances at

Wolf Trap in Vienna.

He was not the only one who launched

a new

career after

meeting Ordman. Gail Humphries Mardirosian, now the chair of the

Performing Arts Department at American University, was recruited to

help teach arts in the schools and credits her career to Ordman.

"She could see the value of the

arts and

necessity of

the arts in lives of children," Mardirosian said. "Anyone in her life

was part of her family. She remained a source of inspiration throughout

the years. She changed my life."

Other lives were changed, too.

Ordman was

searching for

a piece of land for a properly equipped school playground for children

with disabilities. A developer had the perfect parcel nearby, but he

was reluctant to donate it. She learned that the developer, who was

Roman Catholic, had a daughter whose marriage had fallen apart.

The only hope to end the nuptials in

the good

graces of

the church was an annulment from Rome. Ordman started with a call to

Georgetown Law School, and after a series of calls to ever-higher

church officials, the daughter got an annulment and the school got a

playground, according to her son.

And then there was the time in the

late 1960s

when Ordman decided to run for Democratic precinct captain in Wheaton.

"She recruited my brother and his

friends to go

out

campaigning for her on Halloween night, which fell just a few days

before the Nov. 4 election," her son said in an article for the

Christian Science Monitor report. "They were organized so that one of

them would knock on the door of each house in the precinct, and say,

'No, I don't want candy, the treat I want is for you to vote for Evelyn

Ordman for precinct chairman on Nov. 4.'

"Some voters told my mother later

that they were

really

impressed when the kids actually politely declined to take any candy.

(Later that evening, of course, they had a Halloween party in our

basement, complete with all the candy they wanted.)"

Her interest in the world did not

stop with

herself.

"She was very enthusiastic, extremely supportive and had a tremendously

can-do spirit," said Gary Ratner, who discussed his Bethesda

citizens-based school reform organization with her. "When she took an

interest in somebody, it was like having a one-person cheering section."

© 2004 The

Washington Post

Company

|

|

|

|

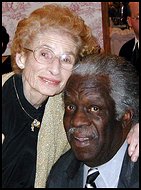

Evelyn Ruth Ordman

with jazz

musician Keter Betts, who recalled how she

sweet-talked him into volunteering in schools. "She wants something

done . . . she just comes and talks to you and bam, it gets done," he

said. (Family Photo)

|

|