Page 7 - Efrat

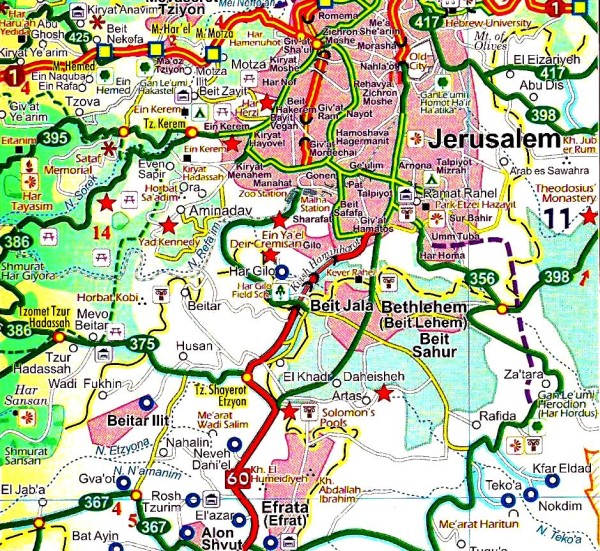

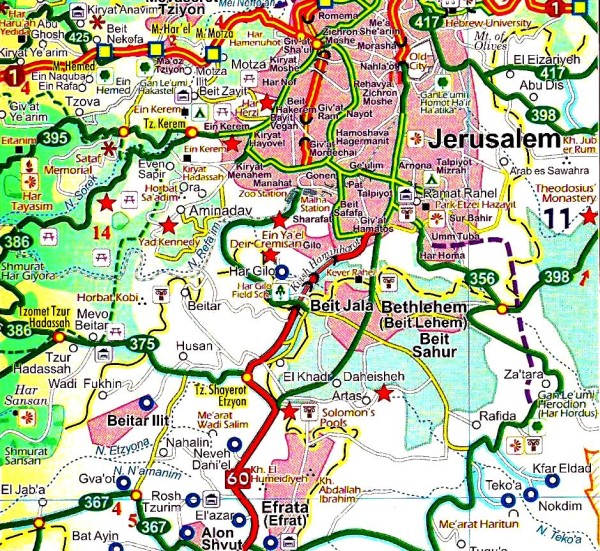

Here is a map of some of the area we have been talking about. You

can see Jerusalem, going south is Bethlehem, on its south edge is the

"Daheisheh" refugee camp.

Let's go a bit further south, to the settlement of Efrat.

Efrat is within the bounds of the 1948

to 1967 "West

Bank", and is regarded by its Jewish residents as a suburb of

Jerusalem. The "security boundary" includes it on the Israeli

side. From the point of view of an American developer or city

planner, working without regard to politics, it is a very logical place

to have a suburban development, and it is a very attractive modern

suburban city, with shops, synagogues, and attractive plantings.

It is on the top of a string of small hills, with pretty views of the

surrounding agricultural land. There are convenient road

connections for those commuting to jobs in Jerusalem or even Tel

Aviv. The population of immigrants from the US is large

enough to make it attractive to Americans, and I am told and believe

that most residents have come because they find it an attractive and

convenient suburb and a good place to raise children.

The founders of Efrat, we were

told by the local spokesman, arrived at a time when it was still

expected that there could be peaceful coexistence, cooperation,

and friendship between the Israelis and Palestinians. I recall

that feeling well; it was very prevalent when I was first in Jerusalem,

in 1971, and the economy was booming. The first land was purchased

peacefully and Palestinians from the surrounding villages often

worked in Efrat.

Later, of course, the Intifadas

came. The expansion of Efrat became controversial (now, even the

central Israeli government discourages Efrat from expanding onto a

neighboring hillside) and there was a real fear of attacks from radical

Palestinians.

The Palestinian view of these

settlements is, of course, different. Many object to any

settlement of Jews in areas Israel conquered in 1967.

Israelis point out in reply that the border of 1948 to 1967 were never

recognized by any of the surrounding countries; why is Israel supposed

to be bound by them now?

Land titles are often obscure: between 1918

and 1948 the British never developed a system for recording the old

Turkish land titles, and deeds may well be disputed. And as in

the US, decisions by governments to annex land or change its use are

not always welcomed by the landowners. For example, Israel prefers to

expand Jerusalem suburbs onto land not being actively farmed. They can

show you photographs showing that "this field was abandoned, not being

farmed, when we rezoned it." The locals retort: "Hey, grape vines

can get a disease. When they do, you cut them down and leave the field

fallow for a year or two before replanting. We can show you

photographs showing the grape vines here two years earlier."

Everyone agrees that Efrat sits

on a major aquifer, and controls a major source of water for the area.

Was this coincidence? Was it because a builder found it easier to build

a new town where there was readily available water? Was it because a

nationalist Israeli saw a chance to impede Palestinian access to

water? I don't find it useful to answer such questions. My

wife Eunice has been a mediator in the Memphis court system: she

can tell us that in many disputes, trying to agree on past facts is

neither easy nor even necessary. It is necessary for both sides

to be heard; for both sides to feel the other has heard their

story. And then it is often possible to figure out and even

agree on what should happen in the future.

What should happen in the future,

in Efrat? That's a hard one. It, and other settlements

like it, tend to "break up" Palestine. It is very hard to imagine

a system of roads that allow Jewish areas and Palestinian areas both to

be connected, even using bridges and tunnels. In a truly peaceful

solution, it might be possible to have scattered pockets of Jews living

among the Palestinians, fair sharing of water, cooperating police

forces that served two different populations, with appropriate

solutions for people who have lost homes and fields to war, security

barriers, and urban development. But that sort of peace may be a

great many years in the future.

One possible way of hoping for a

nearer-term solution, but possibly equally far-fetched, is the

following thought: Israel has shown it has the money and the

technological ability to build new communities, and large quantities of

housing, remarkably quickly. The recent absorption of about a million

arrivals

from the former Soviet Union was remarkable. It would be possible to

provide new housing for the Palestinians in refugee camps. It would be

possible to have a working economy in the West Bank and Gaza, so that

people could have jobs and schools to go to instead of bomb factories

and protest meetings. Some Palestinians will not get their

original homes and land back, but homes and water and agricultural

land can be found for those that want them. And if some Jewish

settlements have to be relocated, new ones can be built and those

people also may have to live in places that are not their first

choice.

Peace will require

sacrifices from a lot of people, including American Jews like me -

because it will cost a lot of money, and a lot of that money will have

to come from people like me. But I'd rather spend it on houses and

desalinization and irrigation and building schools than on guns and

bombs and wars, and compared to the cost of the guns and bombs and

wars, it is really not prohibitively expensive.

Ordman Net Home

Israel/Palestine Info Home

CONTENTS:

Page 1: Introduction

Page 2: Kfar Shalem

Page 3: Duheisha Refugee Camp

Page 4: Universities

Page 5: The Wall / Security Barrier

Page 6: Bethlehem

Page 7: Efrat

Next> Page 8: Hebron

(More to come)